Solutions versus strategies

We often don’t know the outcome of our strategies until we’ve completed several months of collecting, monitoring, analyzing, and iterating. In the meantime, you can conduct A/B tests to feel more confident in your decisions, but they aren’t always worth the time or resources. What you should really be focusing on when designing new strategies and solutions is problem identification. This should be your first milestone, and the source of true confidence in future decisions.

Remember that strategies will change over time – and that’s okay. You should welcome this type of evolution: strategies will change more often than you might want them to, and there is a certain degree of comfort and vulnerability in accepting the unknown. Similar to how you might use Waze to provide different routes for getting from point A to point B during rush hour, problem identification serves a crucial purpose in defining goals and setting the strategies that will lead you to achieve them.

Caveat: not all problems require rigorous identification.

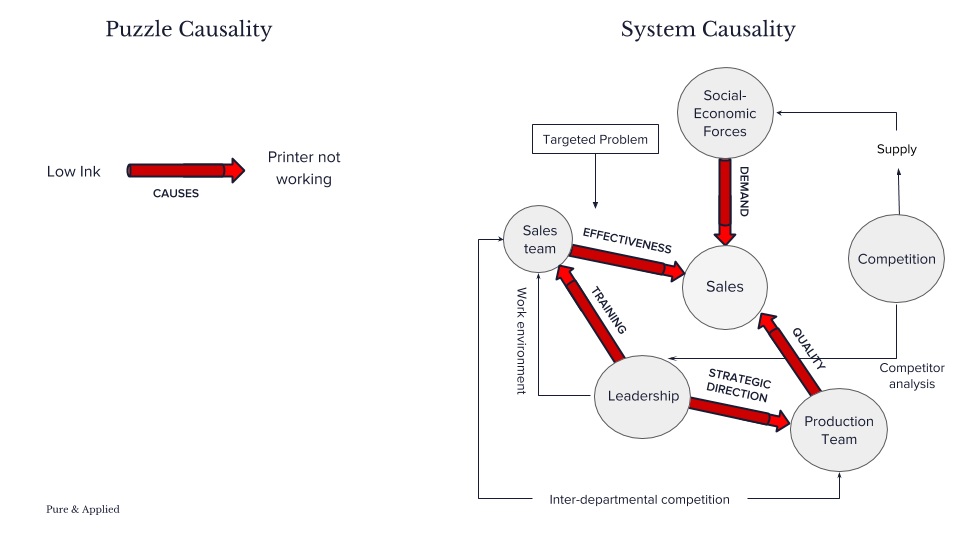

It’s important to understand that not all problems require problem identification. A game of chess is a problem, a printer that has run out of ink is a problem. In both these cases, the problem is clearly defined and the set of possible actions is understood. This does not necessarily mean that success will come easily – understanding the rules of chess does not mean that you are good at it, just that the problem is clearly defined. These are puzzle problems: cause and effect is understood and the path to success is easily identified.

Puzzle problems can be contrasted with open-ended issues where success exists on a gradient. Take voting as an example: the set of possible choices is sometimes more limited than you would like, the connection between your vote and your goals (ex. reduce CO2 emissions) is vague, and whether you voted ‘correctly’ is untestable. In this kind of scenario, framing your choices becomes very important for meaningful decision-making.

System problems

Consider the following situation: product X is not selling well in the US market. At first, problem identification may not seem to be an issue, but upon more careful examination, it becomes apparent that this problem doesn’t provide a causal explanation. There may be a number of intertwined explanations as to why X is not selling: it could be that the sales team is ineffective with its outreach, or that the company’s brand isn’t aligned with the target market’s values. Maybe we are in the midst of a deep recession and no one has the money for non-essential products. The crucial point is that the real subject of enquiry – the organization that makes and sells product X (1) – is a complex system.

It may be a helpful metaphor to consider the initial problem statement (that product X is not selling well in the US) as a symptom of a disease. Diseases rarely present with a single symptom, and the symptoms themselves are never the actual problem in need of attention. Just like a doctor, the goal of a solution designer is to identify a plausible cause and effect explanation for problems, creating an action plan that targets the sickness rather than the symptoms. Without a causal explanation, a statement like “product X is not selling” is as useful as a doctor observing that their patient is coughing.

Problem definition is therefore essential. As is the case in medicine, treatment following a misdiagnosis will be ineffective and may even cause additional harm. It is therefore important to be wary of assuming that you’ve understood a problem too quickly. It is entirely possible that sales are low because of the sales team, but to make that assumption is like a doctor hearing a patient cough in the waiting room and diagnosing them with bronchitis.

The limits of solution-design

So far, we’ve explored the type of context where problem identification matters. It’s equally as important to understand the limitations of solution-design in these kind of contexts.

First off, many problems are not entirely solvable. Sales challenges, for example, can never be ‘solved – only improved. For companies and organizations with finite resources and time, the act of choosing which problems to solve is itself one of the defining problems that will determine their success. Second, in a complex system such as a company, most problems will have innumerable causes. The purpose of defining a problem is to identify the most significant causal factors that you can influence (2). Third, be aware that implementing a solution within a complex system can have unintended consequences.

Problem definition in practice

How can problem definition be improved in practice?

1. Organizations are diverse, so be cautious about implementing stock solutions

One of the key issues that plagues both researchers and problem solvers is external validity. Just because a solution works in one context does not mean that it will work in another situation. If your organization is seeking to solve an important problem, it is worth taking the time to investigate the problem thoroughly, rather than quickly implementing solutions that have worked for other organizations.

2. Build a shared understanding of the problem

This issue is worthy of its own article, but it’s important to remember that organizations are comprised of different groups (e.g. the sales team, the marketing team, the HR department). Involving the right teams and stakeholders in the problem identification process can help expand the understanding of a problem via additional perspectives, while nurturing company culture through collaboration. Failure to work as a team can cause resentment and conflict when a solution is implemented (i.e. the unintended negative consequences mentioned above).

3. Explore alternative explanations and frames

When trying to identify a problem, it is easy to fall victim to a number of cognitive biases. Some key biases include overconfidence, availability heuristics (placing greater weight on things that more easily come to mind), and confirmation bias, among others. Furthering the medical analogy, physicians are prone to these same errors, as discussed in the article “Five pitfalls in decisions about diagnosis and prescribing”.

One way to break out of these constraints is to purposefully ask two important questions: "Are there any explanations that we haven’t explored?” and “Are there alternative ways to frame explanations that we have explored?”

Here’s an example of the latter: tenants in an office building are complaining about the elevators being slow. The managers of the building decide to ‘solve’ the problem by putting mirrors in the elevators, after reframing the slow elevator issue as “people are bored waiting in the elevator” (example drawn from Are you solving the right problems?).

Recommended Readings

This article by HBR echos examples of company problem identification done right.

This article by Deloitte serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of framing questions and removing our own biases for effective problem solving.

This article by Dwayne Spardlin for the HBR was a seminal work in defining problems of the type explored in this article.

* * *

Footnotes

(1) Which exists and sells its products within a larger social-economic system.

(2) In those cases where the most significant causal factors of a problem are beyond your influence, it may be time to move on to a new problem.

This blog was co-authored with D. Ryan Workman, Public policy professional and organizational strategy expert. Frisbee golf enthusiast.